Immersive cinema is the future

This article is also available in:

![]() Italiano (Italian)

Italiano (Italian)

Current cinema, a modern derivation of the ancient analog, has five characteristics: static and linear structure, dual mode, episodic, mainly in third person and not interactive. We will see later what each of these voices means, while I continue to think about what the cinema of the future will be, about immersive cinema, and how to make a good prototype.

I started this article on a Swiss train, and finished it at Barcelona’s charming Espai Joliu. I love trains, being able to work or relax while moving between two locations. Among my corporate benefits is the general season ticket for all means of transport in Switzerland: my luck. A few days off from work, I take the opportunity to reach Domodossola (the first Italian town across the border), or wander the length and breadth of the country of the Helvetians, which reserves surprises and magical corners almost everywhere.

Indice

How important is immersion in the cinema of the future

I am part of the line of thought, now increasingly in vogue, which imagines a single evolution for cinema: immersive cinema. According to purists, or “traditionalists”, cinema must be left as it is. But we have already seen that, after all, they are not necessarily right.

As you may have noticed, I am not at all cadenced in publishing articles on my blog. I don’t like online editorial plans, I prefer quality over quantity, avoiding in-depth articles only to come out “Friday at 7”. This article took me days of research, maybe more, and clearly blogging is not my primary activity, but it has resulted in a roundup of ideas and characters that I hope will be a definitive answer to the question: how will the cinema of the future be?

Few have seriously tried to innovate it, and in this article we will get to know some of them. Certainly not for lack of a market. Rather for lack of resources, lately more and more projected to the lucrative, and more manageable, virtual world.

This article follows from: Innovating modern cinema

Advantages and disadvantages of modern cinema

I reflected on the advantages of cinema as it is conceived today:

- It can be used on the move, even here on the train.

- Other actions can be taken, delegating the mere role of companion to the audiovisual.

- It can be used in company.

I ask you for other advantages, I really want you to comment. Turning to the disadvantages:

- The methods of use have been updated little for decades.

- It is not able to “fill” all the senses of the viewer.

So let’s create a system, using already existing technology, able to minimize these disadvantages.

Analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of modern cinema

1) You can watch cinema on the go

Clearly, “old style” cinema by definition is destined for theaters. However, in order to recover costs, a production must be usable by as many people as possible. A good substitute for the small screen are virtual reality viewers, which allow you to view stereoscopic 360 ° videos.

2) You can do other things while watching a movie

Here virtual reality, at present, shows all its limits due to the complete isolation it creates. Bypassing this limit is perhaps possible with augmented reality, or with a serious upgrade of existing virtual reality technology.

3) You can watch a movie in company

By designing an update of the cinema system intended as a “cinema”, for decades there has been a technology used above all in scientific dissemination: the fulldome, ie projections in a dome. However, the same system is not new to film experimentation, even by great masters of the past.

4) The methods of use have been updated little for decades

The first disadvantage of cinema is rather an observation. If, on the one hand, great directors or companies have brought immense innovations in shooting methods (think ofAvatar di Cameron con una Motion Capture all’ennesima potenza, o alla Industrial Light & Magic che insieme ad Epic ha dato il là ad una seria Virtual Production), poco si è fatto per le sale.

The transition from film to digital, without wanting to diminish it, is comparable to the change of our home TV. Best quality, lower distribution costs, maximum stereoscopy but otherwise everything as before.

5) It is not able to “fill” all the senses of the viewer.

A century ago, a great innovator, today’s cinema fails to offer that “something more” compared to other more modern tools.

When looking at an iPad or modern TV, the field of view covered by the image is approximately 25°. The cinema screen, on average, covers a field of view of 50° on the 360 of the sphere (it depends a lot on the position in the room). It is necessary to increase it, if you really want to return to offer that “wow” effect, due to the immersion, which is worth the trip and the ticket.

The acoustics are already very good; Dolby Digital systems allow excellent immersion. What is missing is still the feel, the smell and, why not, also the taste.

Why virtual reality is not popular

I’ve been trying to figure out why you never want to put a helmet on, and a recent University of Glasgow paper / survey by Laura Bajorunaite, Stephen Brewster and Julie R. Williamsoncertainly helped.

The paper deals specifically with the use of VR viewers in public transport, which in itself is a place of frequent cinematic use. But the discourse is expandable, with the necessary adaptations, a little more generally.

At the base there are clearly reasons of personal safety, but also of comfort. Social acceptance is also still a long way off, making VR users “stupid” in the eyes of other passengers. Progress is still being made to make one’s virtual world more integrated with reality.

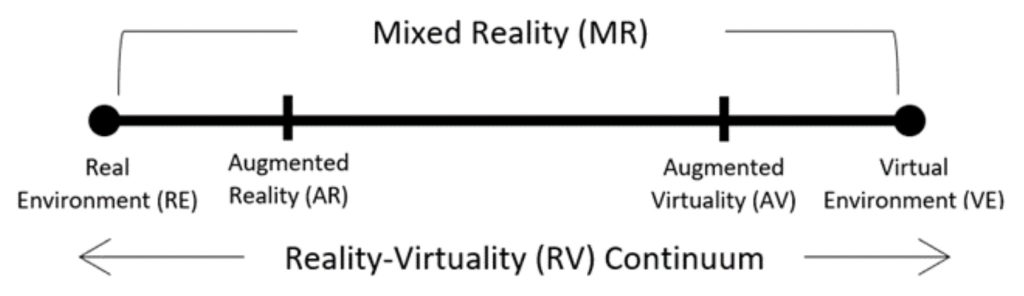

For example, occasionally throwing an eye to the real world with the cameras installed on the viewer, or having indications on the positioning of other human beings in real space, can reassure us. A complete Virtual Reality must be avoided in favor of Augmented Virtuality; as already defined in 1999 by Prof. Paul Milgram in its line of continuity from real world to virtual world.

I invite you to read the paper to learn more, but the concept we must take into account is that total immersion is a problem.

Immersive cinema

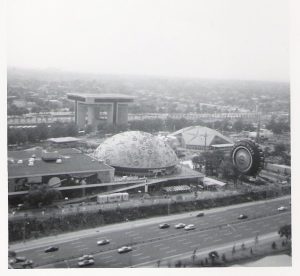

We have already covered the history of fulldome cinema in detail (article available here), but To the Moon and Beyond, is considered by many to be the first immersive film in history. The first to cover a 360 ° field of view, filmed with the Cinerama technique using a single fish-eye lens, on 70mm film at 18 fps, and projected onto the roof of a large dome about 30 meters high.

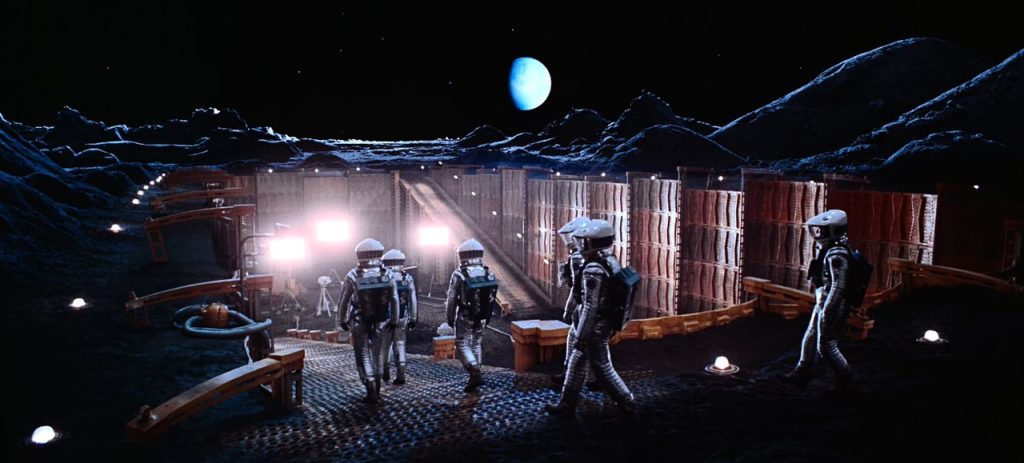

If its use was still somehow “didactic”, we moved away from the astronomical canons to bring instead a greater involvement towards the issues of transport. The film also influenced Stanley Kubrick, hiring its creators as VFX consultants for the legendary 2001: A Space Odyssey. Lester Novros and our next protagonist: Douglas Trumbull.

Douglas Trumbull, a mission: to save cinema

Douglas Trumbull was a man with a great idea:movies can be more realistic and more immersive than they already are.

I would have liked to meet him in person, he was a myth for me. I tried to write to him a couple of times, offering to visit him at his Trumbull Studios in the countryside of Massachusetts, but unfortunately I got no reply. Perhaps the addresses I had were no longer current, perhaps he was too busy as well as old. I don’t know, the fact is that he is no longer with us except through his studies that still have the time to change the history of cinema.

He was one of the greatest experts in the world of special effects, first analog and then digital. Creator of amazing graphic masterpieces in the top of last century Hollywood production (2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Star Trek …). After starting to smell the decay of traditional cinemas, he devoted his entire life to finding a solution. Which he too found in immersive cinema, as a true pioneer.

Perhaps due to his analogue habit of always finding physical and real ideas rather than creating a new app or a new system to monetize users’ time while they are alone or at home, Douglas was a multinational craftsman. He certainly had art in his DNA: his father, Donald (Pappy Trumbull to friends) had been involved with VFX since the 1930s. Not officially accredited, he worked on The Wizard of Oz from 1939.

It was during the filming of 2001: A Space Odyssey that, only 25, Doug created the legendary psychedelic color stream “Slit Scan” based on the technique developed shortly before by John Whitney for Vertigo.

Immersivity is the future of cinema

I report part of an interview made by Filmmakermagazine.com to Trumbull himself.

If you look at the industry, it is moving more and more towards immersive experiences. Take virtual reality, for example; the problem is that people don’t want to wear the headset. Immersiveness is what TV cannot offer; when 3D took off, everyone started making 3D TVs. But now nobody makes them anymore.

I think the problem was miniaturization. When you look at a 3D image on the big screen, you have a 6 foot (1.82 meters) figure standing in front of you, while when you put it on a TV screen you have like a 6 inch (15 cm) figure. When I took the projects we were working on and played them on the TV screen to see what they looked like, the effect was completely lost.

Douglas Trumbull

Magi Pod: innovating the cinema

Douglas Trumbull in his later years developed with Trumbull Studios a system that united many of the key points for the renewal of cinemas. A redesign of both shooting and projection systems. At its core, 120fps 4K projection solves a problem Kubrick already denounced over 50 years ago: 24fps blur is obnoxious and unrealistic. For this already 2001: A Space Odyssey was shot at a high framerate, although almost no room was equipped for reproduction.

Trumbull wanted to bring back the magic he himself felt in visiting the curved screens of the Cinerama in childhood. But technically there were many problems to be solved.

Troubleshoot 3D projection

To begin with, stereoscopic projection requires halving the framerate (or doubling the projectors, which would be uneconomical). This means 60 fps projection per eye.

Then there is another, more concrete problem: in 3D films both images (right and left) are recorded simultaneously. But they are then projected one after the other, alternately (right, left, right, left eye etc …). There is therefore a small difference that is not visually perceptible, but not negligible from our unconscious. Solution? Record the two images with a distance of 180 degrees / shutter, then alternately, as they will then be projected. This solves a second problem, which concerns the “cinematic look”.

The high framerate is not in fact used in cinema because it makes the product too similar to video and TV. Trumbull then concluded to increase the flicker effect originally given by the cinematic 24 fps thanks to the recording of the left and right frames of the stereoscopy with 180 degrees / shutter distance. In addition to reducing the luminance of the screen (in the Magi equal to 14 FtL, less than 50 lux), but not reducing the gain of the screen itself.

The entire Magi patent aims to increase audience involvement: it translates into projection in the Magi Pod.

A small cinema, 70 seats ll in the best viewing area; toroidal silver screen (curved both horizontally and vertically) with 3x gain to increase contrast and therefore immersion; 32 speakers for enhanced surround effect; rotary subwoofers capable of reaching 1 Hertz, creating a “4D” effect with the absurd vibrations.

Trumbull’s years of experience leading the technical departments of the biggest blockbusters, in a single, magical, immersive cinema. If knowledge must always go forward, it cannot be ignored in the design of the cinema of the future.

Cross reflections in fulldome cinema

By designing a fulldome cinema, the differences with the Magi Pod are many and fundamental. The Magi does not in fact fill a dome, but only a part of it. And you cannot simply “enlarge” the field of view to compose 360 degrees. There is a first big problem: cross reflexes.

Anyone who has worked with high gain projection screens will have realized that a silver, 3X amplified screen is a kind of mirror. Reflecting both the light coming from the outside and the same image projected from one side to the other in the case of a convex screen. A problem that also experienced Steven Spielberg’s 1991 production, Back to the Future: The Ride; fulldome re-proposition of the original Back to the Future.

By limiting the radius, and keeping the spectators within an optimal viewing angle (therefore in central positions) the problem is reduced to almost zero. But a complete sphere must necessarily be a white screen with a reflection ratio of less than 1, or the solution is still to be studied. And in this case we will certainly have to do practical experiments in the near future.

Immersion in the cinema of the future

In fact, almost every previous study we talk about in this article is in some way linked to the digital world. But, as you may know, I am a staunch supporter of sociability and the return to real life.

The room will have to resemble a space and time machine, where you will enter a totally new dimension for the duration of the screening, and from which you will come out with a complete experience. Above all, in company.

The world is heading towards the conquest of space, which will initially be within the possibilities of a select few. Others will want to try new experiences, and they will have to do so while necessarily being on the ground.

Five senses for immersive cinema

The viewer will have to be the protagonist, so the narrative will also have to change. We remember well: without disturbing the intuition, the sixth, we still have five other senses.

Today’s dual cinema manages to cover only two of them: sight and hearing. And, especially for sight, we can do a lot to improve the situation. Reading the number of Wired Italia of December 2021 (magazine that is always full of interesting ideas) I found this paragraph in an article by Henry Jenkins (lecturer at University of Southern California, director of the comparative media studies program at MIT in Boston for more than 10 years; not the last of the arrivals):

I am convinced that the metaverse will not be the future both because devices such as Oculus viewers are terrible (especially for those who, like me, wear glasses), and because it is not the visual experience that guarantees the highest level of immersion, but that audio and haptics, as evidenced by decades of studies and pioneers such as Metthew Shifrin and Nonny de la Peña.

Henry Jenkins

Jenkins’s idea, similar to mine in many ways, intrigued me to get to know musician Matthew Shifrin.

Matthew Shifrin: Legos and the cinema of the future

Matthew Shifrin is a young musician, blind from birth. Since he was a child, a Lego enthusiast, these allow him to experiment, touch, “see” without eyes. Thanks to touch, and therefore also to Legos, he can understand how the world works; as did. According to his eloquent example, he will never know what the Statue of Liberty is like without climbing it. And climbing the Statue of Liberty can be problematic… Therefore, a small Lego statue perfectly fulfills its function.

It is his thirteenth year of life. At the door rings Lilya, family friend. She approaches Matthew with light steps, looks at him and says cheerfully: “I have something for you!”. Matthew, confused, smiles at her as the woman places a package in her hands. The child opens it, touching a sheet entirely written in braille: these are the instructions for building Lego structures by himself.. His eyes shine, he is so happy. And he wants to get to work right away.

Lego for the blind

The story leads him to found, years later, “Lego for the blind“. An association, with its website, where you can download instructions like these for about thirty Lego products. And convinces the same company to include them in new products. He also created a system to help the blind to climb the rocks, really brilliant.

Definitely an interesting character; but you may be wondering why we talk about him in an article on the cinema of the future. I understand you, I was so taken by his story that for a moment I did it too. Then I remembered where I wanted to go.

In his TEDx Talk at Suffolk University, starting at minute six, he explains it well and in a very funny way.

Blind people in the cinema of the future

The point is: if the world manages to be immersive for a blind person, cinema can never be immersive in a similar or equal way to the real world if it is not for a blind person. The fact that the cinema of the future can be enjoyed in a better way also by people with disabilities, can only be an excellent and stimulating side effect.

While studying singing and accordion at the New England Conservatory in Boston, he continues to look for ways to make modern life more suitable for people like him.

In episode 3 of his Blind Guy Travels podcast, Matthew describes going to the movies with his friend Ben. The need to have Ben to describe the visual part of every single scene, and even thus not have a complete idea of the whole, leads him to create with his university a tactile device for the cinema.

With the support of the New England Conservatory’s Entrepreneurial Musicianship Department, Matt and his business partner have developed a programmable vibrating vest integrated with technology that mimics the sensations of overturning, flying and falling. This allows a new audience to effectively follow the Marvel Daredevil saga, a blind lawyer who becomes a superhero at night.

A few days ago I wrote an email to the conservatory asking for more details on this system, unfortunately without receiving an answer. I plan to comment on this article if I have any news in the future, it is interesting.

We will talk about experiential cinema

I have ready an analysis of the characteristics of current cinema, and of how they evolve in experiential cinema. How the latter is interactive, immersive, algorithmic and other important studies for the purpose of creating our cinema of the future.

But I decided to end the article here, it was getting too long and dispersed. I have already copied the text into a new WordPress post, which I will complete as soon as possible and publish.

I renew the invitation to comment, to share doubts and criticisms, and above all to participate in this innovation if you like it. You can also write to me, my address is [email protected]. See you soon!

There are two things I love about modern cinema. I love how they are ready to watch anywhere and anytime you want to. It is very convenient for busy people like me. I also love that you can stream them with people you want to watch together.